Summary:

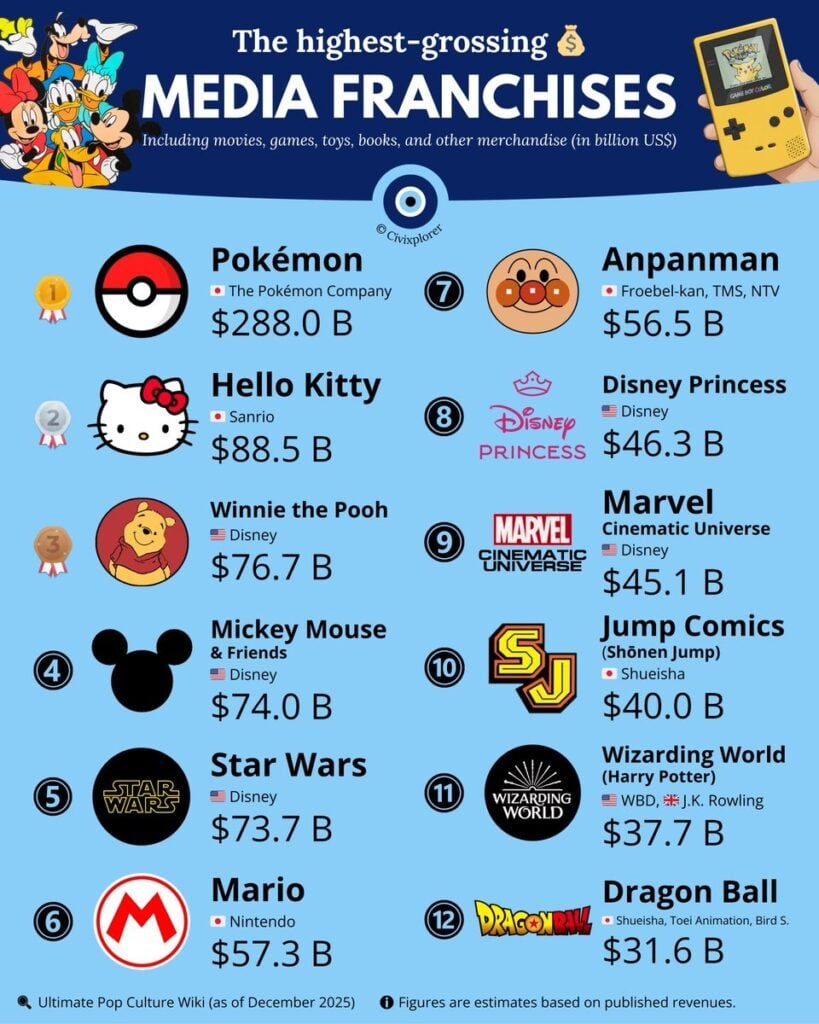

We love a simple ranking, especially when it mixes childhood nostalgia with “wait, how is that worth more than that?” energy. A recent infographic from Fandom’s Ultimate Pop Culture Wiki puts Pokémon at the very top of the all-time revenue mountain, with familiar giants like Hello Kitty, Winnie the Pooh, Mickey Mouse, and Star Wars packed right behind it. Nintendo shows up twice in the conversation, too, because Mario lands high on the list and reminds us that games can be the spark that ignites decades of toys, spin-offs, theme park deals, and brand licensing.

But the real story is not just who’s in the top ten or top twelve. It’s why these franchises earn what they earn. For many of the biggest names, the “money button” isn’t box office, and it’s not even the latest game release. It’s merchandise and licensing, the steady drip of plushies, pajamas, lunch boxes, limited collabs, collector items, and character branding that turns a cute face into a global business. That’s why Winnie the Pooh can sit alongside space battles, superheroes, and plumbers, and nobody should be shocked. We also need to keep one foot on the ground, because these totals depend on what gets counted and which snapshot of data a list uses. If one list places Mario above Anpanman and another flips them, that doesn’t mean anyone is lying. It usually means the counting rules and data sources aren’t identical.

Lifetime gross rankings and why they matter to us

Rankings like this hit the brain like a theme park funnel cake: we know it’s a lot, we know it’s messy, and we still want another bite. The fun is the contrast. We expect Star Wars to print money because lightsabers and blockbusters feel expensive. We expect Marvel to be huge because superhero movies have been a cultural weather system for years. Then a quiet character brand like Hello Kitty strolls in, waves politely, and reminds us that a franchise can earn mountains of money without needing a cinematic universe or a dramatic third-act twist. These lists also spark a second kind of curiosity: not just “who won,” but “how did they win?” That’s where the real entertainment starts, because it forces us to notice the parts of fandom spending that are easy to overlook, like the everyday purchases that happen far away from opening weekend hype.

Where the numbers come from

When an infographic claims “highest grossing media franchises,” we’re usually looking at a stitched-together quilt of public data points. That means revenue estimates pulled from company reports when available, industry write-ups, licensing discussions, box office totals, game sales, and other public signals that can be gathered and compared. It’s not one magical spreadsheet that every brand agrees on, because companies do not publish the same level of detail, and they definitely don’t all publish it in the same format. So we’re relying on compilation work, and that compilation work is only as clean as the underlying sources. The good news is that this approach can still be useful, as long as we treat the totals as best-available estimates rather than a courtroom verdict carved into stone. The list can be right in spirit even when the exact decimals are fuzzy.

What “grossing” usually includes

“Grossing” is a wide net, and that’s the point. It can include box office and home video for film series, but it can also include game sales, in-app spending, toys, apparel, publishing, and licensing deals. Pokémon is a great example because it is not just one product category doing the heavy lifting. It’s games, trading cards, merchandise, movies, mobile spending, and a constant cycle of new creatures that keeps the whole machine humming. Meanwhile, something like Mickey Mouse and Friends can lean heavily on retail and licensing, because the character brand itself is the product. That difference matters, because it explains why two franchises can be neighbors on a ranking while earning their money in totally different ways. One might be a blockbuster sprinter. Another might be a marathon runner wearing comfy shoes and never stopping.

The merchandise multiplier

If box office is a fireworks show, merchandise is the power grid that keeps the city lit every night. Merch is often where a franchise becomes truly “daily life.” Think about how many ways a character can appear: backpacks, bedding, mugs, seasonal decorations, phone cases, cosmetics collabs, school supplies, and the endless universe of gifts for kids and collectors. This is why Pooh and Hello Kitty belong in the same sentence as Star Wars. They’re not trying to win on theatrical spectacle. They’re winning on presence. When a brand shows up in stores year after year, across price points, across age groups, and across countries, the total can grow into something that feels unreal. It’s not one huge purchase, it’s millions of small ones that add up like raindrops filling a swimming pool.

The estimate trap and how to avoid it

Here’s the part that saves us from internet arguments: different lists can use different assumptions, and that can shuffle positions. Some sources treat an umbrella brand as one bucket, while others split it into sub-franchises. Some count certain licensing categories, others exclude them. Some update more frequently, others freeze at a certain “up to 2023” or “up to 2024” snapshot. That’s why one recent ranking can show Mario above Anpanman, while another data table places Anpanman ahead of Mario. The healthiest way to read the numbers is to focus on the big picture: which franchises consistently sit in the top tier, and what their business mix looks like. Treat the order as a scoreboard, not a sacred text.

The infographic’s top tier, explained

The recent infographic that sparked this conversation lays out a lineup that feels like a pop culture dinner party where every guest is famous. Pokémon sits at number one, and the rest of the top tier is loaded with brands that have lived in multiple generations of childhood and fandom. The surprising part for many people is not that these names are huge. It’s that the gap between “popular” and “financial titan” can be wider than expected. Popularity is a spotlight. Revenue is a whole building full of accountants, factories, licensing agreements, retail relationships, and a thousand little decisions about how a character shows up in the world. The top tier is where popularity turns into infrastructure, where a franchise stops being a hit and starts being an ecosystem.

Pokémon

Pokémon being at the top makes sense once we remember what Pokémon really is: a collecting loop disguised as a world. Every new generation adds creatures, and every new creature is basically a seed that can grow into a card, a plush, a figurine, an anime episode, a mobile event, a backpack, and a Halloween costume. It’s like the franchise keeps inventing new “units of cuteness,” and each unit can be monetized without feeling forced because fans actually want the thing. The trading card game also adds a second engine, because it turns characters into objects with value and rarity, which keeps collectors engaged in a way that doesn’t depend on a new movie every year. That breadth is why Pokémon doesn’t just lead. It stays hard to catch, in the best possible way.

Hello Kitty

Hello Kitty is the quiet masterclass in licensing. There’s no need for a giant cinematic storyline when the character can live on nearly anything you can print, stitch, or sculpt. The brand’s strength is flexibility. Hello Kitty can be cute, classy, ironic, minimalist, loud, pastel, luxury, or supermarket-cheap, and it still feels like Hello Kitty. That means it can partner with wildly different products without breaking its identity, which is basically the dream scenario for a long-running character franchise. In revenue terms, this is less like a roller coaster and more like a river. It flows. It doesn’t need a single “big moment” to justify its scale, because the scale comes from constant, global, everyday presence.

Winnie the Pooh

Winnie the Pooh is the perfect reminder that the toddler economy is undefeated. Kids grow fast, which means parents and families buy a lot of “firsts” over and over again: first plush, first pajamas, first backpack, first bedtime book, first sippy cup with a character on it. Pooh fits that world effortlessly because the brand is soft, friendly, and timeless, so it never feels out of place in nurseries and gift aisles. That doesn’t mean adults don’t love Pooh, because they do. It means the franchise has a built-in renewal cycle that keeps sales steady even when there isn’t a headline-grabbing media release. It’s not about hype. It’s about comfort, familiarity, and the kind of gentle character design that never goes out of style.

The classic giants in the same room

After the top tier, the list keeps stacking legendary names like it’s building a “greatest hits” playlist you can’t skip. Mickey Mouse and Star Wars sit here as two very different kinds of power. Mickey is the symbol of an entire entertainment empire, which makes the character brand feel almost like a logo for a lifestyle. Star Wars is a story-driven franchise that still manages to earn like a retail juggernaut because its iconography is so strong, and its fans love collecting physical reminders of that galaxy. Seeing them close together in a ranking is a nice reality check. There isn’t one correct recipe for financial dominance. There are multiple recipes, and some of them are more about characters than stories, while others are the opposite.

Mickey Mouse and Friends

Mickey Mouse and Friends is the ultimate “always on” franchise. Even when there isn’t a big new movie moment, the characters are still everywhere, because they’re designed to be evergreen. Mickey doesn’t need a plot twist to sell a t-shirt. The character is the message. That makes the brand unusually resilient across time, because it can adapt to new styles and new generations without needing to reinvent itself. It also benefits from Disney’s broader retail machine, where parks, stores, collaborations, and media channels reinforce each other. Think of it like a giant wheel: the more it turns, the easier it is to keep turning. That kind of momentum is hard for most franchises to replicate, because it’s built over decades, not quarters.

Star Wars

Star Wars earns like a franchise with two faces. One face is the film and TV side, where releases create big spikes in attention and revenue. The other face is the collector and merchandise side, where lightsabers, helmets, ships, and character designs keep selling long after the credits roll. Star Wars also has a rare advantage: its world is instantly recognizable. You can show someone a silhouette of a stormtrooper, a Jedi robe, or a TIE fighter, and they know what it is. That recognizability translates to product power, because it means the franchise can sell “symbols” as much as it sells stories. The brand becomes wearable, displayable, giftable. In revenue terms, that is a superpower, because it stretches the franchise beyond release cycles.

Nintendo’s headline duo

Nintendo showing up in this conversation with Pokémon and Mario is not a fluke, it’s a strategy that’s been paying off for decades. These franchises start with games, but they don’t stay trapped inside a console box. They turn into characters and worlds that people carry into real life, from toys and clothing to theme park experiences and collaborations. The recent infographic that kicked this off even places Mario as high as number six, which is a bold reminder that the mustached plumber is not just “famous.” He’s commercially massive. And unlike some franchises that rely on a handful of huge releases, Nintendo’s big brands tend to benefit from steady engagement, where new games, re-releases, and evergreen popularity keep the engine warm year after year.

Mario’s money machine

Mario has the rare ability to feel like everyone’s character. Kids meet Mario through bright, friendly games. Adults remember him from earlier eras and keep buying because nostalgia is a powerful little gremlin that lives in the wallet. The franchise also spreads across genres like it’s changing outfits backstage: platformers, racing, party games, sports games, RPGs, and more. That variety matters because it keeps Mario relevant even when one style of game is not dominating the moment. Mario is also easy to merchandise because the design is clean and iconic. The hat, the mustache, the colors, the silhouette, it’s all instantly readable. That’s how a character becomes a symbol, and symbols sell forever.

Why games keep the engine running

For Mario, games are the heartbeat. Even when movies or theme park expansions get the headlines, games are the steady drum that keeps the brand active and visible. A new release can drive hardware sales, spark social buzz, and pull in new fans who then buy merch or pick up older titles. Games also have a unique advantage compared to film: they can be replayed, shared locally, streamed, speedrun, modded in conversation, and revisited for comfort. That creates a long tail where a title doesn’t just “come out and leave.” It sticks around. When the foundation is interactive, the relationship with fans tends to be deeper, and deeper relationships usually mean more touchpoints where someone chooses to spend.

The sleepers that shock newcomers

Every big list has at least one name that makes people blink twice and lean closer to the screen. That’s usually because the franchise is gigantic in a specific market, or because it earns in categories that don’t make a lot of noise online. Anpanman is a perfect example. If you didn’t grow up around it, you might not instinctively place it next to Star Wars. But if a character is a cultural staple for families, and that staple translates into constant retail and media presence, the numbers can climb fast. Jump Comics is another kind of sleeper, because it’s not one story, it’s an empire of stories. If you think of it like a magazine label, it’s easy to underestimate. If you think of it as the gateway to countless blockbuster manga and anime properties, it starts to click.

Anpanman

Anpanman is proof that domestic dominance can compete with global fame. The franchise is deeply rooted in Japan’s family entertainment landscape, and that’s where the revenue strength comes from. It’s not chasing worldwide blockbuster status as its main plan. It’s showing up consistently in the places that matter for its audience: kids’ media, toys, character goods, and the everyday ecosystem of family purchases. When a franchise becomes a default choice for young children, it gets a steady stream of demand that doesn’t need international social media hype to exist. In other words, it’s less like a worldwide stadium tour and more like a hometown residency that never ends. That “never ends” part is the money part.

Jump Comics (Shōnen Jump)

Jump Comics is a reminder that the label matters when the label owns the pipeline. Shōnen Jump is tied to manga and comics on a scale that has shaped pop culture for decades, and that scale can translate into huge lifetime totals when you count publishing impact and the wider commercial ecosystem around major series. It’s also a brand that acts like a launchpad. A hit series can turn into anime, films, games, merchandise, and collaborations, and the Jump umbrella benefits from that broader effect. The tricky part is that different rankings handle this differently. Some treat Jump as its own bucket. Others focus on individual series. Either way, the “surprise” is usually just unfamiliarity with how massive serialized publishing can be when it becomes a global habit.

Modern mega brands

Then we hit the modern heavyweights that feel obvious, but are still worth unpacking because their money mix is different. Marvel is a machine built for cross-media expansion, and it’s been doing that at industrial scale for years. The Wizarding World is a strong example of how books can become a full commercial ecosystem, especially when movies, merchandise, and experiences keep the world alive between major releases. Dragon Ball sits in a special spot, too, because it has a long history and a global fanbase that spans multiple generations. These are not “one format” franchises. They’re worlds that can be repackaged, revisited, and sold in different shapes, which is why they keep showing up on lists even when the cultural spotlight shifts to the next shiny thing.

Marvel

Marvel’s modern dominance is built on a simple trick that isn’t really a trick at all: make each story feel like part of a bigger world, then give fans reasons to stay invested across years. That’s the entertainment side. The commercial side is that recognizable heroes are incredibly merch-friendly, and a large character roster gives Marvel endless flexibility. If one hero cools off for a while, another heats up. If one movie underperforms, the brand still sells toys, apparel, collectibles, and collaborations. Marvel also benefits from being modular. You can love Spider-Man without loving everything. You can watch the big team-up movies and ignore smaller releases. That “choose your lane” structure keeps the audience wide, and wide audiences tend to spend in more categories.

Wizarding World (Harry Potter)

The Wizarding World is a strong example of how a story can become an identity. The books created the emotional foundation, and the films turned that foundation into global spectacle. From there, the franchise expanded into merchandise, games, experiences, and a steady stream of licensed products that keep the imagery in people’s daily lives. What makes it especially durable is how distinct the visual language is. Wands, robes, house crests, and iconic locations are easy to turn into products that feel meaningful rather than random. Fans don’t just buy “stuff.” They buy signals of belonging. That matters because belonging sells all year, not just on release dates. And once a franchise becomes a go-to gift category, it gains a second life as a retail staple.

Dragon Ball

Dragon Ball’s staying power is all about momentum and legacy. It’s been around long enough that parents can introduce it to kids, which is basically the gold medal in franchise longevity. The series also has a punchy, instantly recognizable style, from characters to transformations to the broader aesthetic of its world. That recognizability translates well to games, collectibles, and merchandise, because fans want to own the moments they remember, not just rewatch them. Dragon Ball also benefits from a competitive, community-driven fandom culture, where discussions, rankings, and nostalgia debates keep the brand alive even between major releases. When fans keep talking, the franchise keeps selling, because conversation is free marketing and fandom is a habit.

Why rankings change depending on who made the list

If two lists disagree, it usually comes down to rules, not reality. One list might be tied to a specific “up to 2023” snapshot, while another is more recent. One might count certain categories differently, or combine and split brands in ways that change the order. A recent Nintendo-focused roundup based on an Ultimate Pop Culture Wiki infographic, for example, places Mario at number six, ahead of Anpanman, while other tables that cite “up to 2023” totals place Anpanman above Mario and shift the rest of the top ten accordingly. That’s not a reason to throw the whole idea away. It’s a reason to read the fine print with common sense. The consistent truth is still clear: Pokémon sits at the top in these compiled rankings, and a familiar group of character and story giants dominate the upper tier because they monetize across many categories, not just one.

Conclusion

When we look at the highest-grossing media franchises, we’re really looking at who figured out how to live in people’s lives, not just on their screens. Pokémon dominates because it keeps creating new reasons to collect, play, and connect, and because its products stretch across games, cards, and everyday merchandise. Hello Kitty and Winnie the Pooh remind us that softness and familiarity can be just as powerful as explosions and plot twists, especially when licensing makes a character feel omnipresent. Mario shows how a game-first franchise can become a global symbol, with new releases keeping the brand fresh while decades of recognition keep the merch machine rolling. And the names that surprise us, like Anpanman or Jump Comics, are a great reminder that local cultural giants can generate astonishing lifetime totals. If we keep one eye on methodology and one eye on the big picture, these rankings stop being trivia and start becoming a map of how pop culture actually earns.

FAQs

- Why is Pokémon usually ranked number one?

- Because it earns across multiple huge categories at once, especially merchandise, games, and trading cards. The franchise also refreshes itself constantly with new generations and new creatures that become new products.

- How can Winnie the Pooh be above some action-heavy franchises?

- Merchandise and licensing can outperform box office by a lot over time. Pooh is a steady retail staple, especially for kids’ products and gifts, which adds up year after year.

- Why does Mario’s position change between lists?

- Different rankings use different data snapshots and counting rules. Some tables place Anpanman ahead of Mario, while the recent infographic shared in late 2025 places Mario higher.

- Is “Jump Comics” one franchise or many?

- It’s an umbrella label tied to publishing and a wider ecosystem of series. Some rankings treat it as one bucket, while others focus on individual series under the umbrella.

- What’s the biggest mistake people make when reading these rankings?

- Assuming “grossing” means box office only, or assuming every list uses identical rules. The smart move is to check what categories are included and what time window the totals reflect.

Sources

- Pokemon and Mario in top ten of highest grossing media franchises in history, My Nintendo News, December 30, 2025

- Japan’s content industry ramps up overseas market development, Nikkei Asia, February 4, 2025

- The World’s Top Media Franchises by All-Time Revenue, Voronoi, April 20, 2024

- The Transformation of the World in Film. Relations between the Form of Film and Society, Revista UNAM Internacional, November 15, 2024